Andrew Kerr

ActBlue, the fundraising platform that commands a virtual monopoly over Democratic online fundraising, accumulated a cash hoard of at least $172.8 million by the end of 2020 while simultaneously claiming it needs “tips” from donors to keep its lights on.

ActBlue states on its website it asks for “tips” because it does not profit from processing contributions made through its platform, but ActBlue’s credit card processing arm has reported paying taxes on its business profits every year since 2013, IRS records show. From 2013 through 2020, ActBlue’s PAC collected $147.7 million in “tips” from small-dollar Democratic donors, FEC records show.

“If ActBlue’s claims of tips being essential to their operation are in fact false, and donors are making contributions based on those claims, this raises serious legal concerns,” Former National Republican Congressional Committee General Counsel Chris Winkelman told the DCNF.

“The Department of Justice has shown a willingness in recent years to charge 527 political committees with conspiracy to commit wire fraud through false and misleading representations,” Winkelman added, referring to recent prosecutions against scam PAC operators. “State deceptive practices laws also exist to protect donors from being duped.”

Politicians and political committees that raise funds on ActBlue are charged a 3.95% fee on every dollar they raise, paid to ActBlue Technical Services (ABTS), the network’s credit card processing arm. ABTS is a 527 nonprofit political group that reports its finances monthly to the IRS.

ActBlue states publicly that its 3.95% fee “solely covers the credit card processing fees,” but there are actually two elements to the fee — a 2.45% credit card transaction fee and a 1.5% in-house “ActBlue Service Fee,” which, ActBlue said in 2007, “pays for pretty much everything behind the website.”

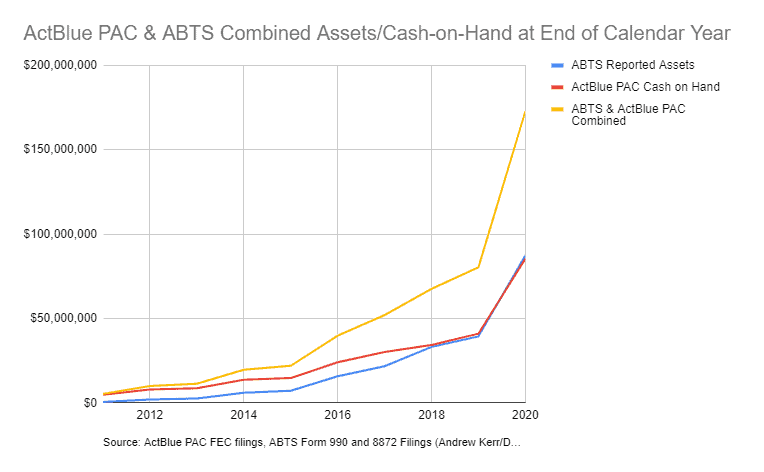

ActBlue’s processing volume ballooned from $173.1 million during the 2011-2012 campaign cycle to nearly $5.1 billion during the 2019-2020 campaign cycle. The combined cash hoard of ActBlue’s PAC and ABTS grew from $5.3 million at the end of 2011 to $172.8 million by the end of 2020, IRS and FEC records show.

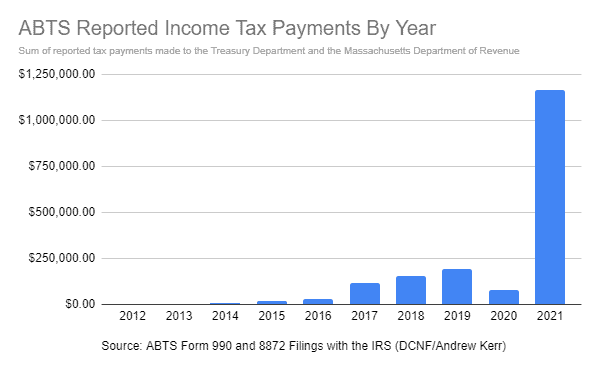

ABTS has reported paying a combined $1.8 million in income taxes on its profits since 2013, with most of that — $1.2 million — having been paid in April, according to the group’s Form 990 and 8872 filings with the IRS.

Despite ABTS reporting that it is paying taxes on its business profits, ActBlue states unequivocally on its website that it does not profit from processing donations.

“As a nonprofit, we use tips from donors to pay our bills,” ActBlue states on its website. “We do not profit from any of the contributions we process.”

“We’re a nonprofit, and we can only keep our tools up and running with the support of small-dollar donors like you,” ActBlue states on another page titled “What are ActBlue Tips for?”

“We pass along a 3.95% processing fee on contributions to the groups using our platform,” the page states. “ActBlue does not make money off of donations.”

ActBlue declined to comment on the figures presented in this story after being given multiple opportunities to provide a response. ActBlue also refused to provide the DCNF copies of ABTS’s Form 1120-POL it has filed with the IRS, a document the group has submitted out every year since 2012 to “report their political organization taxable income and income tax liability,” the IRS states.

The “1120-POL’s are not public documents,” ActBlue spokeswoman Morgan Hill told the DCNF.

Former Republican National Committee Counsel Charles Spies said state attorneys general will likely want to investigate ActBlue’s fundraising tactics.

“State attorneys general are taking an active interest in fraudulent claims in political committee fundraising and will likely want to investigate Act Blue’s claims here,” Spies told the DCNF. “There’s nothing per se wrong with making a multi-million dollar profit, but misleading donors about the issue raises legal and ethical concerns.”

When someone contributes to a federal political candidate or group through ActBlue, the funds are first distributed to ActBlue PAC, which then forwards the entire donation to the earmarked recipient. ABTS then bills the recipient candidate or group for 3.95% of the contribution.

Immediately after someone donates to a federal candidate or group through ActBlue, the site asks donors to give an extra “tip” to ActBlue’s PAC.

“ActBlue is a nonprofit fundraising platform that thousands of Democrats and millions of grassroots donors are counting on to help them power change in their communities,” the tip solicitation reads. “Will you chip in with a $1 tip?”

ActBlue’s PAC received $147.7 million in “tips” between 2013 and 2020, FEC records show. ActBlue says it uses “tips” provided to its PAC to fund customer support and other types of direct assistance to federal political campaigns that raise funds through its platform, the group said on its blog.

The process works similarly when someone donates to a state or local political candidate through ActBlue, with the primary difference being that ActBlue solicits a tip for ABTS instead of its PAC.

“ActBlue Technical Services is a nonprofit that builds the fundraising platform that thousands of Democrats and millions of grassroots donors are counting on to help them power change in their communities,” the ABTS tip solicitation reads. “Will you chip in with a $1 tip?”

ABTS reported receiving a total of $24.4 million in contributions in its annual Form 990s between 2011 and 2019, the latest available year.

It’s not clear why ABTS solicits tips when it’s already paying taxes on its business profits. It’s also not clear why ABTS doesn’t use its surpluses to help cover ActBlue PAC’s expenditures. ActBlue declined to respond to a detailed list of questions from the DCNF.

ActBlue and its GOP counterpart, WinRed, are already under investigation by the attorneys general for New York, Minnesota, Maryland and Connecticut for their use of prechecked boxes that enrolled small-dollar contributors into recurring donations, a practice that led to a wave of fraud complaints during the 2020 elections, The New York Times reported in July. No such charges have been filed against ActBlue of which the DCNF is aware.

WinRed operates similarly to ActBlue, but it’s structured as a for-profit company and doesn’t solicit extra tips from donors. WinRed recently lowered its credit card processing fee to 3.94%, one basis point below ActBlue’s 3.95% fee.

A WinRed spokesperson told the DCNF that the company is fully sustainable and has room to grow its operations at its reduced processing fee.

Chris Wilson, the CEO of the conservative polling and data analytics firm WPA Intelligence, added his opinion that it’s unethical for ActBlue to be reaping a profit from its contribution fee while telling small-dollar donors otherwise.

“These guys are lying to the donors about what’s really happening to the money they’re collecting,” Wilson said. “And the ‘tip jar’ to get a little extra from each donor is really the icing on the cake.”

“This is common on the left,” Wilson added. “Everyone whose profession is politics has to make a living, but the left wants to do it while maintaining this illusion that it’s all not for profit and somehow volunteer. So they play this shell game.”

ActBlue had to dip into its cash hoard slightly during the first half of 2021 following a record-breaking 2020 in which the network processed over $4 billion worth of contributions. ActBlue ended the month of June with a combined $170.5 million shared between its PAC and ABTS, according to FEC and IRS records.

However, ActBlue is on track to blow past its previous records as the 2022 midterm election season heats up. The first half of 2021 was “the biggest start to an election cycle in ActBlue’s history,” the group said in July, having raised over $602.1 million in the period, more than twice the amount the group raised in the first half of 2017.

“Even more impressive: More donors gave on ActBlue in the first half of this year compared to the first half of 2019 when the presidential primary ramped up, signaling a continued broad engagement from donors this cycle,” ActBlue said in a recent blog post.

ActBlue’s Processing Fee ‘Pays For Pretty Much Everything’

ActBlue’s 3.95% processing fee on gross contributions has remained unchanged since it was rolled out in 2007, a year the group’s processing volume was a blip on the radar compared to what comes through its doors today.

When ActBlue first launched in 2004, the group charged a much lower processing fee of 2.4% plus 10 cents per transaction. ActBlue added at the time that it expected the fee to go down to as low as 2.0% plus 10 cents as processing volume increased.

“Remember, we’re a PAC, not a business. Our goal is to get as much money to Democrats as we can,” ActBlue stated on an archived version of its website in 2004.

By February 2005, ActBlue had increased its fee to 3.15% on contributions made to single recipients. Again, the organization stated it expected rates to fall to 2.9% as its processing volume increased.

ActBlue announced in 2007 that it was increasing its fee to 3.95% because its initial fees were unsustainable. ActBlue said a for-profit company called Auburn Quad, operated by ActBlue co-founders Matthew DeBergalis and Benjamin Rahn, would receive the fee, which consisted of two elements: a 2.45% credit card processing fee and a 1.5% Auburn Quad fee that would stay in-house. The announcement contained no language indicating the increased fee rate would fall as ActBlue’s processing volume increased.

The 1.5% Auburn Quad fee, ActBlue said in 2007, “pays for pretty much everything behind the website: computers, the programmers, and the coffee; or in specific terms, all the additional transactional costs borne by AQ to receive and remit contributions on your behalf.”

ActBlue currently states on its website that it charges an “ActBlue Service Fee” of 1.5% on each gross contribution.

ActBlue stressed in 2007 that it and Auburn Quad were two distinct organizations with two different sets of leaders. This, ActBlue said, would help the groups navigate any potential conflicts of interest.

“There can be a real tension between ActBlue and AQ, whose goals are certainly similar but not precisely the same,” ActBlue wrote on its blog in 2007. “This is good. It keeps us moving forward and honest to our mission. ActBlue has a phenomenal Board of Directors (a majority of whom have no role in Auburn Quad) who help us negotiate the natural conflicts of interest and make sure that ActBlue’s political goals are never compromised.”

Auburn Quad would later become ABTS in 2009. “Everything is going work the same way it did before,” ActBlue said in a blog post announcing ABTS’s launch.

But in 2021, the four individuals that serve as directors of ABTS also serve similar roles in ActBlue.

Erin Hill serves as executive director for both ActBlue and ABTS, according to the group’s latest Form 990 filed in November 2020. ActBlue co-founders DeBergalis and Rahn also serve on the board of directors for both organizations, as does as Marc Laitin, according to the Massachusetts business registration files for the two groups. And ABTS clerk Nichole Paulding serves as ActBlue’s director of operations.

ActBlue’s 3.95% processing fee has remained unchanged, despite the fact ActBlue’s contribution volume during the 2019-2020 election cycle was a staggering $5.1 billion, an 8,000% increase from its processing volume of $62.2 million in the 2007-2008 election cycle when the higher fee was first introduced.

2020 in particular was a breakout year for ActBlue, with the network processing over $4 billion through its platform, a nearly 4-fold increase from the previous highs of $1.1 billion set in 2018 and 2019.

ABTS’s monthly 8872 filings with the IRS show the group received $166.3 million in 2020 and reported expenditures of $118.3 million during the year — $100.1 million of which were classified as Credit Card Processing Fees.

ABTS’s estimated operating surplus of $48 million for 2020 would have been enough to cover every penny of ActBlue PAC’s reported 2020 operating expenditures of $26.3 million, and the group would still have had $21.7 million left over.

It’s not clear why ActBlue has not lowered its 3.95% processing fee as its contribution volume has increased over the years.

- Bucs Dominate And Still Feel They Can Play Better

- Two Florida Teachers Arrested After Drinking, Entering Wrong Home And Shooting Man

- Frontier Airlines Denies Boarding For Florida Family Taking Child To Boston For Medical Care Over Mask

- Levin: Florida Gov. DeSantis Is ‘Very Impressive,’ And ‘Done A Helluva Job’ Handling COVID

- Walmart Goes “Woke” Pushing CRT, Telling White Cashiers And Shelf-Stockers That They Are The Privileged Members Of ‘White Supremacy System’

Support journalism by clicking here to our GoFundMe or sign up for our free newsletter by clicking here

Android Users, Click Here To Download The Free Press App And Never Miss A Story. It’s Free And Coming To Apple Users Soon